Lunar Occultations of K2 Stars

Background

I had an epiphany in early 2016: The moon goes through the K2 fields. I mean, of course it does by construction. K2 has to point along the ecliptic due to using the solar wind as a 3rd axis stabilizer. The moon travels along ecliptic. In hindsight, it is very obvious.

This provides a unique opportunity: Lunar occultation studies of K2 targets.

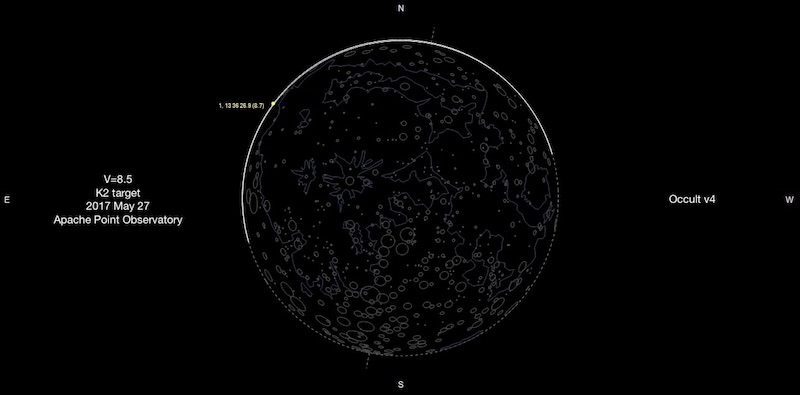

Such a project for community observers of occultations was described by the Occult software maker, Dave Herald, in this forum comment as an idea pitched by James Lloyd. The banner figure above is an example occultation in May 2017 of a K2 target observable from APO, as computed by Occult v4.2.0

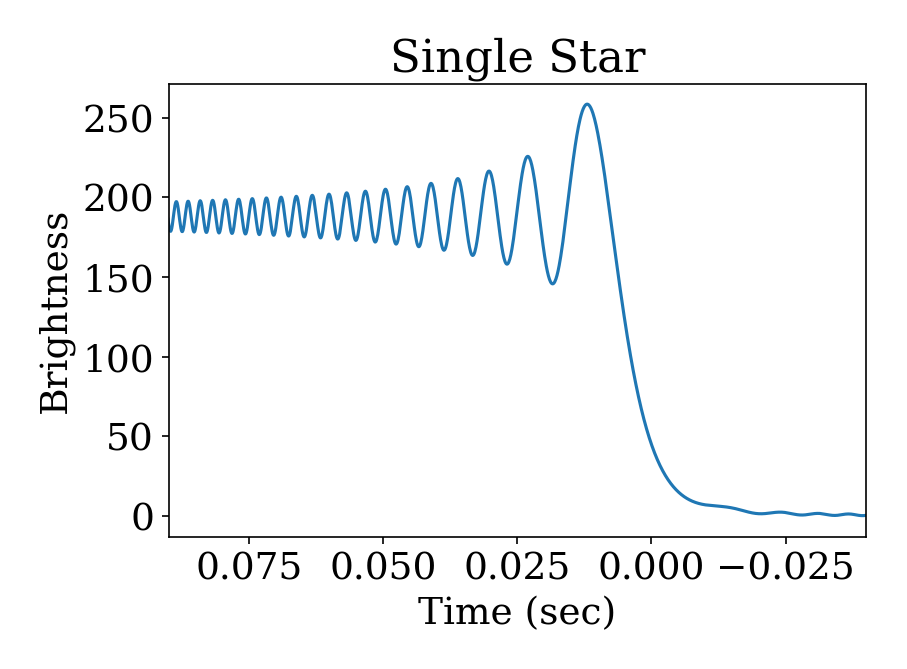

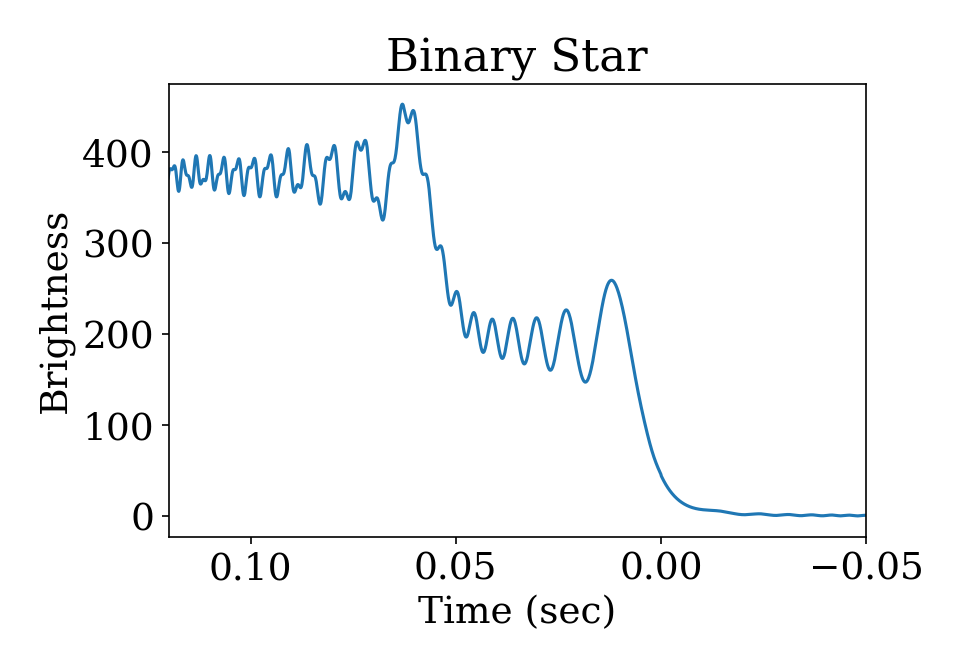

Lunar occultations can be used to estimate the angular diameter of background stars. It can also be used to determine if a star is actually a binary! Check out these toy examples I coded up:

Occultations allow binaries to be detected at milli-arcsecond separations, assuming the stars are separated along the direction of occultation, and can detect companions up to 11 mag fainter! This means occultations could even be used to detect exoplanets with next-generation large telescopes.

Here is a nice review of the methodology and technical considerations from 1994 by Richichi, where the author notes the field of occultations has been relatively stagnant for 20 years. Unfortunately more than 20 years hence, the same is largely true, and LO remain a fringe technique for stellar astronomers.

Challenges

The first and most obvious constraint to occultation work is the limited number of stars available for study. To wit, we only have 1 moon… though other Solar System body occultations of background stars are frequently observed (e.g. Saturn, asteroids, etc), and are good targets for JWST study - but these are for understanding the Solar System, not stars!

We are also put off by the need for very high speed imaging, often at infrared wavelengths. The events last only a few 100 ms at best, requiring an ultra-fast CCD or video camera system. The Signal-to-Noise requirements of 1-10ms exposures means that occultations are typically only possible for very bright stars, often V<8.

There are other considerations for observing wavelength and telescope diameter, as we are working to measure the diffraction of starlight by the lunar limb.

A Solution?

Fors et. al (2001) described an alternative approach to measuring occultations that particularly appeals to me: drift scanning. (First proposed by Sturmann in 1994) In this approach we read the CCD (camera chip) out at a rate that smears the starlight over many pixels. Since the CCD read is at a constant rate, the time evolution of the event is preserved, often at a resolution of a few ms. Note we are reading the camera while the shutter is open. This is basically the opposite of what SDSS did, where the CCD’s were read at the same rate the sky was drifting by, causing starlight to not smear as the charge moved along the chip, but gave continuous images of the sky. (brilliant!)

This drift-scan approach is attractive because it only requires an off-the-shelf CCD chip, and a little help from some adventurous engineers (e.g. the readout clock speed needs to be tuned, shutter needs to stay open, etc)

With access to lots of telescope time (actually very little time per object!), and minimal changes to a facility instrument, a survey of occultations for K2 sources should be undertaken! I can think of 1 or 2 medium aperture telescopes this would be ideal for…

Future

Drift spectroscopy? Could be possible with a longslit spectrograph (one way time resolved spectroscopy was done in olden days…)